The G20 was established in the aftermath of the 2008-9 financial crisis, as a more robust response to address the challenges of economic global governance. Those challenges having not diminished since it is understandable the group kept its intentions alive and introduced more structure to what was, at the beginning, a rather undefined setting. The current rotating Chair of the Group is Germany, replacing China. In less than a month the G20 will be meeting in Hamburg.

Many consultations and meetings have taken place in different formats following the group Ministers of Finance meeting in March, that amongst others acquiesced to the dropping of a free trade pledge. The Ministers have approved most of the documents for the Summit.

A special consultation organized by Chancellor Merkel on the relations of the G20 with Africa has just taken place in Berlin. It is part of the German government proclaimed “Year of Africa”, that has seen a series of initiatives and announcements being made. Those include a Marshall Plan for Africa, a Pro-Africa private sector drive and a Compact with Africa. The latter is supposed to be integral to the G20 process. No less than 9 Heads of State from the continent joined the Chancellor in historic Berlin in what looked like a launching ceremony. Cote d’Ivoire, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal and Tunisia are the elected few that have been designated “Compact” countries so far. Let us understand what is going on.

The G20 original mission is expanding to a broader agenda that includes many of the development traditional preoccupations, including issues of inequality and good governance. An elaborate proposal prepared by the IMF, World Bank and the African Development Bank lists what countries should do to create enabling investment environments. It is thorough, and makes an informative read. It is true that Africans would like to tap institutional funds to boost their infrastructure development. Nobody can argue about the need for sound macroeconomic management targets. And so on and so forth.

However, what is new? What is different from negotiating a country engagement with the IMF to pass the test for more investment to come? Why is the G20 meddling on this country specific tailor-made proposals around specific policy arguments?

The compact is not about giving money, which one should not argue against by the way, but rather about creating good attractiveness. A sort of beauty contest for distracted private investors to awake up. In which shape and form is this different from what is usually recommended to overwhelmed African administrations?

In one aspect, I think. It offers a narrative of opportunity and hope about Africa and it is giving the continent a lot of attention. It is not clear the entire G20 will buy into the very technical financial engineering proposals being made by the Compact proposal (China for example acts with a different lens and compass, and its investors are less distracted it seems). It is, nevertheless, hard to imagine any G20 member defying the host country “global social responsibility” picked theme.

The African leadership is starting to get used to this type of courtship. Normally they approach these engagements unprepared and with a competitive behavior: “Who has been invited?” This is not helpful. For instance, it is hardly mentioned that the dynamics of the world economy create major problems for Africa that are not a subject of discussion. Negative interest rates are a demonstration of low-risk appetite. Austerity programs can affect demand. Banking regulation is driving major brands out of unwelcomed exposure. Not to mention that by GDP definition Nigeria and Egypt should have been part of a group that only has one African member, South Africa. The combined GDP of the continent should have offered an extra seat to the African Union, since the EU already acts as a full member.

In Berlin, African Presidents one after another spoke kindly of the “Merkel Plan”. This could be interpreted in diverse ways. Of course, it was about recognizing the Chancellor’s interest on the continent (even though they do not like the association of growth with migration, as if the efforts were mostly to arrest flows of young Africans reaching European shores). But calling the efforts by the Chancellor’s name was probably also about the need to denounce these efforts as equivalent to a Marshall Plan.

When General Marshall conceived his plan in 1948, the total amounts of aid from the United States to Europe were about 8% of its GDP. A colossal effort. The equivalent amounts in today’s dollars would be adequate indeed even if it was only based on the German economy. We are not there at all. In fact, we may be somewhere in the discussion about “aid effectiveness” that picked the diligent students for more support. In today’s preoccupations, its equivalent is “investment effectiveness”. More like the mid-1990s talk and less the 1948 Marshall Plan that allowed its originator to be given a Nobel Prize…. for peace.

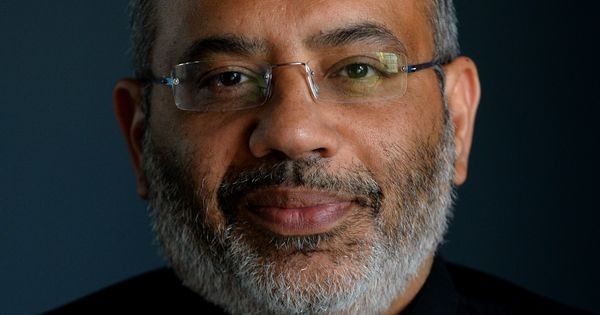

Carlos Lopes is a Professor with the Graduate School of development Policy and Practice, University of Cape Town and a Visiting Fellow with Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford.