By Aurelien Chu and Hafsa Anouar

After two hundred years of stagnation, civil war, and famine, the re-emergence of China as a global economic power has profoundly affected the rest of the world, sometimes challenging and sometimes reinforcing the established international order. Chinese loans and investments, provided by state-owned banks and enterprises as well as private sector actors, have poured into Africa in the past ten years –the visible logos of Chinese construction companies or the markets bustling with Made in China products are an omnipresent reminder. But China’s outwards investments in Africa often have less to do with the context of the target countries than they do with conditions back home. With the recent Chinese stock market turmoil, African leaders should develop strong strategies to prepare themselves for the fluctuations in Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to the continent.

Chinese FDI to Africa and it’s correlations between fluctuations in the Chinese stock market

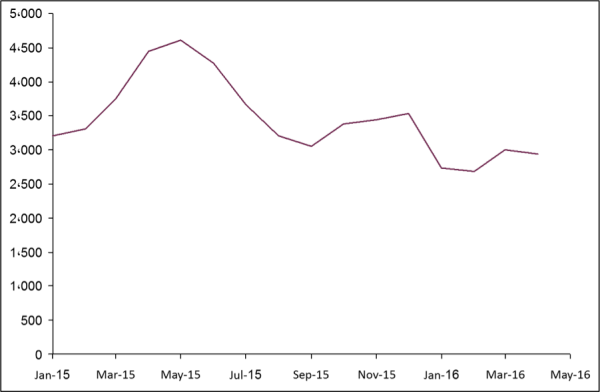

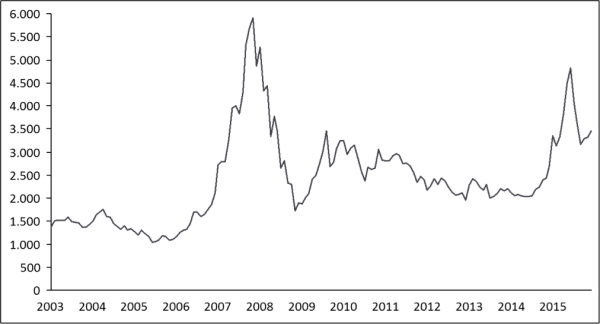

In June 2015, the Chinese stock market bubble popped. By the end of July 7th, shares had fallen by a third, erasing about US$3.5 trillion in wealth. A major aftershock occurred on August 24, known as “Black Monday”, when Chinese stocks suffered their steepest fall in one day, with Shanghai’s main share index closing down at 8.5percent. This turmoil, although not the first in China’s roller-coaster equity markets, demonstrates one of the first major challenges to investor confidence since the financial crisis in 2008. Exhibit 1 demonstrates the fluctuation in the Chinese stock market from 2013 to 2015 and exhibit 2 focuses on the most recent period between January 2015 and May 2016.

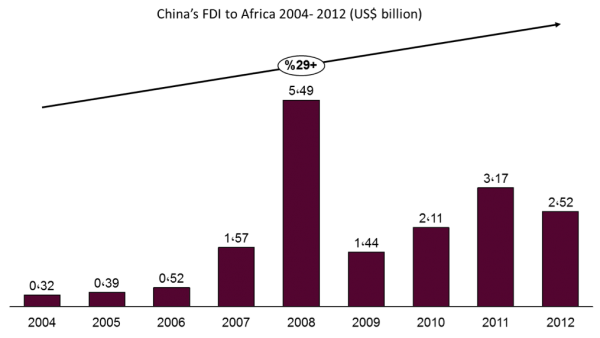

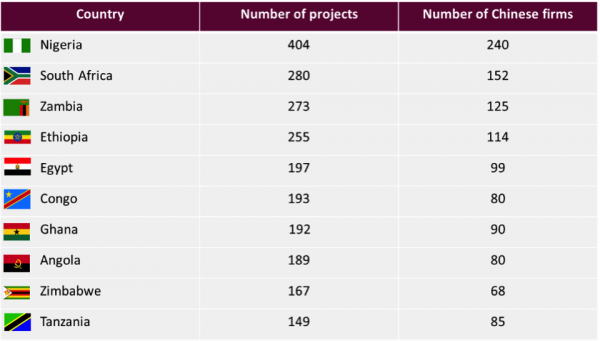

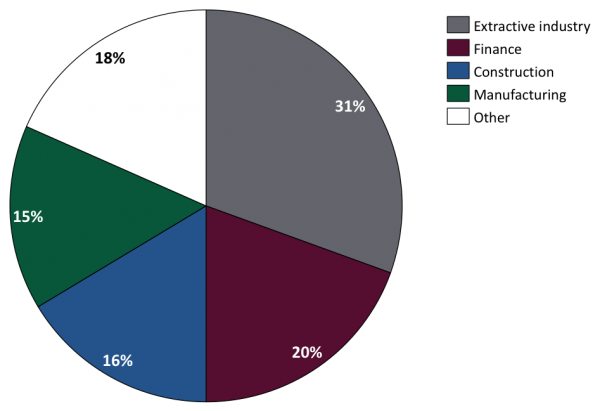

Chinese FDI to the continent has been estimated at $3.5 billion in 2013, and cumulative investment stock at over $25 billion. It should be noted that Chinese FDI to Africa has historically fluctuated by a very significant margin as illustrated in exhibit 3, favored certain countries (exhibit 4), and focused overwhelmingly on four key sectors (exhibit 5) . These characteristics of Chinese investment reflect the country’s comparative advantages (such as the state-owned construction sector’s facilitated access to capital from Chinese state banks) and investment philosophy (e.g. the focus on physical infrastructure-buildout as a backbone for development). However, viewing this phenomenon at a continental scale risks blurring the variety of approaches, interests, and programs that occur under the umbrella mantle of “China in Africa” and which leaves each country uniquely positioned to react to the changing circumstances of the Chinese economy and its actors.

Explanation of this correlation

Looking closely at what happened to the Chinese stock market between 2007 and 2009 and comparing the trend to Chinese FDI to Africa during the same period highlights an interesting correlation. We note comparable movements in equity markets although with a lag of about one year. The lag is a possible result of prior commitments and end of year pledges, or delays in changes in investment behavior from state-owned enterprises. Overall, it is clear that a fall in the Chinese stock market correlates to a decrease in the Chinese FDI to Africa.

Although there is little recent data on Chinese FDI to Africa, the example of past behavior in 2007 and 2009 would indicate that African countries may face a fall in Chinese FDI as capital markets in China tighten.

Recommendations for African leaders to capture benefits and limit the risks of Chinese investment

The uncertain trajectory of the Chinese economy should be cause for African governments to reflect on the course they plan to chart for their countries. Continued turbulence in Chinese markets is likely to motivate previously China-bound investors to look elsewhere for high-growth, emerging opportunities, for which certain African economies are poised to reap major rewards. For many of China’s historical trade partners, however, the Middle Kingdom’s faltering appetite will be a mixed blessing – a short-term pain but a longer-term impetus to exorcise the resource curse afflicting too many of the continent’s economies. We present five main recommendations to African leaders on how to adapt their Chinese investment attraction strategy for better results in leaner times:

- Have a clear vision and reinforce negotiating capacity. When structuring deals with the Chinese, African leaders should have a clear vision for their own country and ensure that the deals they sign tie into these vision to maximize the benefits from Chinese investments in their countries. Furthermore, African governments should invest in high-quality negotiators with a clear grasp of Chinese political and economic dynamics, as well as the technical content of the proposed deals.

- Keep in mind Chinese strategic priorities. When structuring deals with the Chinese, African leaders should keep in mind Chinese interest and strategic priorities. A good example will be deals that speak to China’s food security, which is one of the main priorities for China as its population’s needs for food are continuously growing. Aligning these priorities to the national priorities of African states, including labor rights, trade law, and environmental preservation is crucial to building a sustainable relationship for both parties.

- Use Chinese FDI in R&D to create intellectual capital onshore. Given that investments in R&D are capital heavy and many African countries cannot afford building a strong R&D system, it would be beneficial encouraging the Chinese government or Chinese investors to invest some of the FDI money into R&D in agriculture and manufacturing. A good example is food production. The Chinese can invest in improving agriculture production using technology and training farmers to increase their productivity in exchange of the food produced or an agreed percentage of the profit. It might seem in the short-run that is a loss for African countries, but in the long-run, the physical facilities, the know-how, and most importantly the intellectual capital will be developed onshore. This draws on the experience of China herself in using SEZs to become a trade and manufacturing hub.

- Develop targeted strategies to capitalize on the delocalization of Chinese industries. Many African countries have the potential to become industrial hubs to welcome Chinese factories to open new branches in the continent. However, African leaders need to first create targeted strategies that strike the balance between Chinese investors’ interests and priorities as well as the benefits to the local people. The delocalization of a Chinese IT company in Tanzania for instance would be possible if there are tax incentives and would benefit the local people if the company provides training for local people to join the company. Countries like Morocco and Ethiopia have already attracted Chinese investors looking to diversify holdings away from asset risks in their homeland, transplant lessons learned from successful factories in Asia, or deepen connections in countries they see as successful bets for long-term success. Helen Hai, a Chinese investment advisor, estimates over 80 million potential labor-intensive jobs in China that can be offshored to Africa as Chinese industry transitions up global value chains.

- Reduce investment risks. Emerging markets in Africa may suffer contagion effects as Chinese investment fears reduce the appetite for high-risk gambles across the board. Much of this previously more adventurous capital may, at least in the short-term, seek out “safe havens” such as North American housing markets that can draw on their reputations to attract “scared money”. In order to properly attract return-hungry investors turning away from China and companies opting for geographic diversification, African leaders can focus on identifying and resolving the driving causes of political and business risk.

The re-emergence of China as a global economic power will continue to have a profound effect worldwide. The Middle Kingdom has a fundamentally different approach to collaboration with and investment in African states and societies. But China’s outwards investments in Africa, as in Latin America or Central Asia, often have less to do with the context of the target countries than they do with conditions back home. For the informed citizen and policy-maker alike, it is worthwhile to understand the dynamics of this economic phenomenon, and to contribute to the resilience of national strategies regarding investments from the Asian giant. Inbound FDI was a critical lever for China to carry out her own transition to global economic superpower, and an intelligent African leader will strategically capitalize on China’s FDI for the betterment of their own economy and society.